Why do we eat turkey? A journey through tradition and history

The holiday of Thanksgiving revolves around a bountiful meal whose main course is the roasted turkey. But, have you ever asked yourself how turkey became the centerpiece of this feast?

We have now reached the end of Thanksgiving break and, upon experiencing it for the first time as a foreigner, it is the right time to go a little bit more deeper into this feast.

The “first Thanksgiving” menu originated from a meal shared between Pilgrim settlers at Plymouth colony in what is now Massachusetts in late 1621. And, guess what, there is no indication that turkey was even served. In fact, for meat, the Pilgrims provided wild “fowl,” which were ducks or geese. Why do we chow down on turkey, then?

The answers lie buried in history. By the turn of the 19th century, turkey had increasingly become a popular dish to serve since they were plentiful. It is estimated that there were at least 10 million turkeys in America at the time of European contact. A single turkey was usually big enough to feed a family and these birds were almost always available for slaughter on a family farm. They could be readily killed, as the outcome of the fact that they were generally raised only for their meat.

Italian people would say that these birds are like parsley.

Nevertheless, turkeys were not yet synonymous with Thanksgiving.

The “affirmation of the turkey” in the classical Thanksgiving menu appears to be connected to Sarah Josepha Hale’s Northwood, where she bolstered the idea of turkey as a holiday meal. In her 1827 novel Northwood, she devoted an entire chapter to a description of a New England Thanksgiving, with a roasted turkey “placed at the head of the table.” As a result, nowadays about 46 million turkeys are bred in factories to be eaten on Thanksgiving each year, according to the National Turkey Federation (NTF).

Over the years, the tradition of eating turkeys on Thanksgiving has become outdated and unsustainable, and the farming conditions just keep getting worse.

A survey from 2019 shows that around 736,000 turkeys are killed for food each day in the U.S., and at least 229 million turkeys are raised and slaughtered on American turkey farms annually.

Turkeys (and chickens) are the most cruelly treated factory animals in the meat industry. The Humane Society of the U.S. has launched a campaign to get producers to adopt less gruesome practices during the raising and slaughtering process of the turkeys in order to better their lives while they are alive and to lessen their sufferings.

Despite this, expecting Americans to not eat turkey for Thanksgiving would be like expecting Trump not to get self-tanner anymore. In the words of Suzanne McMillan, a poultry expert with the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), commercial turkeys are “bred to suffer.”

However, the concerns for factory-farmed turkeys’ well-being go beyond the suffering they’re born into, to the conditions in which they’re housed. The birds are crowded in sheds and left with nothing to do except eat. Their breeding, ironically enough, may increase the degree to which they’re impacted by their stressful conditions, weakening their immune system.

A USDA study suggests that the combination of both has made them more susceptible to disease, and that which makes turkeys sick can harm people, too.

From a carbon footprint perspective, turkeys are much lighter on the planet than other forms of meat, particularly beef. But while some may celebrate the week(s) following Thanksgiving with turkey sandwiches and other dishes that make use of the leftovers, a lot of that efficiency is lost in the uneaten meat that goes to waste.

The USDA’s Economic Research Service estimates that when consumers bring home turkey, a full 35 percent of the edible meat, through a combination of cooking, spoilage and plate waste, is lost. One reason why turkey is used so much less efficiently than chicken, which has an estimated “loss rate” of just 15 percent, may be precisely because it’s typically eaten on holidays, when, according to the report, people faced with mountains of leftovers may be more inclined to discard them.

The Natural Resources Defense Council calculates that about 204 million pounds of turkey are thrown away on this one day alone. It is by far the most wasted food on the Thanksgiving table. Also, there is a huge waste in terms of resources used to produce it. It adds up to some 1 million tons of CO2 and 105 billion gallons of water.

More evidence of the intimate relationship between Thanksgiving’s roasted turkey and Americans is given by a brief survey in my journalism class. Not surprisingly, even people who don’t really like turkey would be very disappointed if they wouldn’t have it for Thanksgiving.

Despite Americans’ dining habits, some turkeys do live to see another day, at least at the White House. Abraham Lincoln was the first president that unofficially started the “Pardoning of the turkey” in 1863, by instructing the employees of the White House to save a bird given to him for Christmas. It was his 8-years-old young son, Thomas, who convinced his father not to kill the turkey. In fact, when the Lincolns received a live turkey, Thomas quickly adopted the bird as a pet, naming him Jack. On Christmas Eve, Lincoln told his son that the pet would no longer be a pet, but the boy argued that the bird had every right to live, and as always, the president gave in to his son, writing a reprieve for the turkey on a card.

Since Lincoln’s time, there had been a steady parade of turkeys heading to the White House as the entree for the President’s holiday dinner. Reports of turkeys as gifts to American presidents can be traced to the 1870s, when Rhode Island poultry dealer Horace Vose began sending well-fed birds to the White House. By 1914, after Horace Vose’s death, the opportunity to give a turkey to a president was open to everyone, and poultry gifts were frequently touched with patriotism, partisanship and glee. And so it was that turkeys had become established as a national symbol of good cheer.

President John F. Kennedy pardoned a turkey on November 19, 1963

President John F. Kennedy pardoned a turkey on November 19, 1963

It was President George H.W. Bush who made the turkey pardon official on November 14, 1989, when he announced that year’s bird had “been granted a presidential pardon as of right now.” Since then, turkeys across the United States have rejoiced at least one day a year. With his act, a tradition was born.

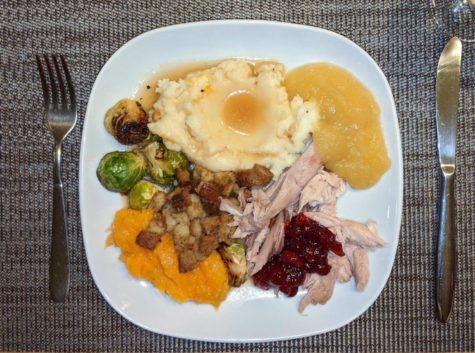

Under here there are some Harwood students and teachers’ pictures about their Thanksgiving dinner. Check them out!